As Ottawa targets mortgage debt, Steve Ladurantaye visits Windsor, Ont., one of the many Canadian cities where there is no single story to be told about real estate values. Instead, two very different tales emerge: In some pockets, prices are skyrocketing. In others, prices struggle to rebound

If there is a real estate bubble in Canada, you sure can’t see it from Drouillard Road.

Three-bedroom houses in this hardscrabble neighbourhood can be had for less than $30,000. Yet there are no offers. Several houses on the busy semi-residential street sit empty, with foreclosure notices posted in their front windows. Nearby, corner stores that used to be open 24 hours a day have shut down.

It’s a far cry from the Toronto and Vancouver markets, where prices are leapfrogging and dinner-party chatter has once again turned to the latest neighbourhood bidding wars.

There’s no contest as to which end of the real estate spectrum is getting attention. Fears of a housing bubble among economists and policy makers seem much more attuned to a handful of high-end metropolitan markets than the norm.

Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s tightening this week of mortgage rules was aimed at preventing Canadians from taking on more housing debt than they’ll be able to handle as interest rates rise, and Mr. Flaherty was careful to say that there is no clear evidence of a housing bubble.

But his policy, which will curb real estate speculation, has ignited a whole new set of concerns: What if prices crash?

The housing sector has been one of the main reasons Canada pulled itself out of recession. Any policy moves aimed at cooling off the market risk pushing prices too far in the other direction – especially because prices are not uniformly high across the country.

The two-tone texture of the market isn’t reflected once numbers are rolled into the national picture.

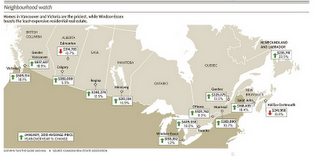

Canadian sales increased by 58 per cent in January compared to the same time last year, while average prices shot up 19.6 per cent. But while the gains in major markets grab most of the headlines, other markets have been far less buoyant. In Quebec and Atlantic Canada, which together represent about a quarter of Canada’s housing stock, prices have been level. There is no sign of a boom-and-bust-cycle.

Talk of a bubble puzzles agents in small- to mid-sized markets such as Windsor, Ont., a hard-hit manufacturing town where business is just getting back to a level that they deem acceptable. Mr. Flaherty’s move to dampen the market seems unconnected to this reality.

“Statistics may show that the market is recovering, but you can make statistics say pretty much anything you want them to,” says Janice Stowe, an agent at Windsor’s Buckingham Realty who specializes in high-end homes. “Yes, things are picking up and homes that would sit for a long time are starting to move again. But to try and cool anything down in the context of Windsor doesn’t make any sense at all.”

Toronto-Dominion Bank economist Pascal Gauthier says the diverse nature of Canada’s real estate market means a U.S.-style bubble is not likely in the works. Those national figures are largely driven by sales in just two cities: Toronto and Vancouver.

“To speak of a bubble, you have to be looking at a pretty broad-based phenomenon,” he said. In the United States, “prices pretty much doubled almost everywhere during the boom,” and that is clearly not happening in Canada.

‘CAUTIOUSLY OPTIMISTIC’

Windsor illustrates the pocket-by-pocket nature of real estate pricing, not only by comparison to the likes of Toronto but even within its own city limits.

A few kilometres away from the crumbling porches of Drouillard Road, Michelle Jamal gives a tour of her luxury condo overlooking the Detroit River. She put it on the market for $1.5-million in the fall when she realized that even a depressed city has effervescent micro-markets as well as bargain alleys.

For two years, Ms. Jamal has been itching to sell the 3,000-square-foot condo and move to a more family-friendly neighbourhood, maybe something with a backyard for her son to enjoy. She nervously watched property values slump as Windsor became the unemployment capital of Canada, opting to sit tight rather than take a big hit on her property, which she bought new in 2005 and then improved with tens of thousands of dollars worth of customization.

Sensing the mood was changing as the recession eased, she contacted Ms. Stowe in the fall and is waiting patiently for an offer. Although there have been few nibbles, she is hanging on to her price and is in no rush to compromise.

“I feel good about selling now,” she says. “I think the prospects are very good, the city is recovering.”

She’s not the only one returning to the market. Sales in Windsor increased by 54 per cent in January compared to the same month a year ago. Prices that had fallen 10 per cent through the recession to an average $156,000 also increased modestly, by 4.3 per cent. It may not seem like much, but in a city that rarely sees big price moves it is a shift that has agents hoping the worst is behind.

Buyers are even starting to open their wallets to buy some of the city’s worst homes, a development agents hope will reduce a backlog of inventory that helps depress prices for nicer homes. Nobody wants to spend $150,000 when tales are circulating about hundreds of homes going for $25,000.

“You’re always hearing those stories, even if for the most part they aren’t really true except for a handful of properties in a few troubled areas,” says Royal LePage Binder broker Frank Binder. He points out the average sale price in the city was $156,000 in January.

“You’re constantly working against the perception that things are very bad – and they were. But the reality is, we’re cautiously optimistic that they have started to turn for the better.”

For the most part, the low-cost homes aren’t being bought by city residents, says real estate board president Anna Vozza, an agent at Bob Pedlar Real Estate. For the last three months she’s been getting calls from investors across Canada who are taking note of the “affordable inventory” and the type of public infrastructure projects that will be needed across the country if housing markets are to regain a sense of stability and manufacturing jobs are to be replaced.

Windsor should benefit from those infrastructure plans. There are proposals for a new river crossing to Detroit, two long-term care facilities, a prison and an engineering complex at University of Windsor. Even WestJet Airlines has noticed the up-tick, she says. The airline announced on Thursday that it will introduce a daily flight from Calgary to Windsor.

“These people see properties listed at very good value and understand the business case of a city that is often the first in and first out of a recession.”

WHAT BUBBLE?

Windsor has taken a bruising in the recession, and most of the country looks more like Windsor than like Toronto.

In Calgary, Royal LePage agent Jim Sparrow points to the distorting effect that areas of Toronto and Vancouver have on the national picture.

Those markets are dramatically different from the rest of the country, he says, thanks to higher demand for upscale properties. “Both those cities have a far broader range of individuals who have been less impacted by the recession,” he says. Wealthy buyers had “put their money away for four to six months last year [but] they came back in droves,” he says.

In addition, both cities are located in provinces where the Harmonized Sales Tax will come into effect July 1. That has added another incentive to buy high-end properties before increased costs come into effect.

In markets like Calgary, “there is no sign of a bubble whatsoever,” Mr. Sparrow says, despite a return to more-normal levels of sales activity.

“I shake my head as I continue to see analysts suggesting that there is a real estate bubble.”

Price escalation in Toronto and Vancouver is not contagious, according to TD Bank’s Mr. Gauthier. Smaller-scale bubbles – which may be appearing in some parts of Western Canada and Ontario – usually reflect real estate speculation, or a particularly healthy economic situation in a specific area, he says.

If a micro-bubble in one city or neighbourhood pops, it will not have the overall economic implications that come with the end of a broad-based bubble.

In general, the patchy nature of the real estate market tends to match the employment situation in various regions, Mr. Gauthier says. In the Greater Toronto Area, for instance, job losses have been far fewer than in manufacturing or resource centres such as Oshawa or Sudbury.

“Understandably, those housing markets must be in a much more difficult situation than others that have rebounded quite firmly,” he says.

With files from Richard Blackwell